Notations 21 Project

Last year I had the privilege of meet with Stuart and Sylvia at a wonderful vegan restaurant in New York City. My daughter, Christine was there as well. What a wonderful conversation we had over lunch…talking about music, composition, food, teaching, ideas in general. It is will be I will never forget. They are such kind, intelligent and generous people as well as great musical geniuses amongst us.

They agreed to to an interview with me as a couple for the Journal of the International Alliance for Women in Music. They had to say so much that was so thoughtful that I thought that I might paraphrase some of it here but please try to get a copy of the IAWM Volume 14, No. for the full article.

Please visit: http://www.smith-publications.com/

“AN INTERVIEW WITH SYLVIA AND STUART SAUNDERS SMITH

BY THERESA SAUER

I had the opportunity to interview Sylvia Smith and Stuart Saunders Smith, two of the most important people in contemporary music today, in New York City on March 2008. Sylvia is a publisher and performer of new music and one of its strongest advocates. Stuart is a composer who couples rhythms and introspective tonalities have been breaking new musical ground and inspiring audiences as well as other composers for years, Together, they form a unique musical power couple; publisher and composer, is an inspiration. With Sylvia, we discussed her dual roles as a new-music publisher and performer (primarily percussion). With Stuart, we spoke about his compositional process and teaching experiences, particularly his creation of the trans-media compositional systems that characterize some of his most flexible and philisophically advanced works, such as Transitions and Leaps. I also had many questions for both of them, exploring their shared ideas and encounters and the relationship that helps make both of them so stong and so fascinating. I learned much about their devotion to artisitic, spiritual, and social progress, and I was stimulated by their ideas and creations. If only all of us had the determination and passion to follow our true beliefs and values, the world might become a better place.

Questions for Sylvia Smith:

Sylvia Smith

1. As a publisher of new music, do you find that a publisher is more of a follower of trends, or a leader in popularization or creation of music?

Smith Publications has always taken a leadership role in new music. I set out, in 1974, to make a publishing house where all sorts of unusual and unique music would be welcome. My first catalog was, for the most part, very unusual. I listed two of Ben Johnston’s microtonal pieces, Herbert Brun’s three solo percussion pieces using computer-designed symbols in the notation system, Stuart Saunders Smith’s piece Here and There that uses an ideogrammic notation for the short wave radio part, and Pauline Oliveros’ Sonic Meditations. In addition to the usual instrumental categories, my catalog had a category called “Flexible Instrumentation and Multi-Media.”

When I opened Smith Publications, I initially planned to select works that were composed completely independently of my needs as a publisher. I realized that same year that to accomplish my goals as a publisher, I would have to take an active role in requesting and commissioning pieces.

I wanted to do something about the dismal state that percussion was in. Percussion, in the Western world, came out of the traditions of the military, marching bands, silent movies and popular shows, other kinds of popular music, always in an accompanying or supporting role, or to add theatrical sound effects. The closest percussion gets to a foreground role is in jazz ensembles, but jazz was fast becoming little more than academic music with standards and basic training.

Brought up on piano, then turning to percussion at the age of twenty-two, I was in a position to compare. I found it shocking that unlike the substantial music on a piano or violin recital, a percussion recital would have cute, etude-like “pieces” or poorly-conceived multiple-percussion pieces (as if they were still being employed in silent movie houses!). Occasionally there would be arrangements of Bach and other classics played on marimba, but were not made with the marimba in mind.

What passed for musical depth was sheer loudness. I found it especially surprising that most percussionists accepted this state of things as “how it is.” It seemed that the serious literature for percussion, compared with other instruments, hardly existed in the 1970s.

In 1974, during my first year as a publisher, I commissioned Stuart Saunders Smith to compose a vibraphone solo that was substantial, with the proviso that “substantial” did not necessarily mean long or fast or loud. He understood what I was asking for, and he composed Links – a three-minute solo for vibraphone. That experience must have inspired him to continue writing for vibraphone, because over the next twenty years he composed eleven ground-breaking works for vibraphone that make up The Links Series of Vibraphone Essays.

In 1987 I asked many composers to turn their abilities to making a snare drum solo to be published in a collection called The Noble Snare. Everyone I asked was so eager to take up this unprecedented challenge. Instead of one volume, there were enough pieces for four volumes. The Noble Snare is used all over the world.

In 2000 I commissioned pieces for a collection of short marimba solos called Marimba Concert. This collection filled the need for short, moderately difficult marimba pieces.

Similarly, in 2005, I commissioned eleven orchestra bell solos to be published in a collection called Summit. I had always thought of the orchestra bells as a missed opportunity. Most percussionists have them and know how to play them, and yet they are rarely called for outside of an orchestral setting. Summit was accepted enthusiastically when I brought it to the International Percussion Convention last year.

2. How do you find music to publish? Would you consider an unsolicited composition?

Composers send me music all the time, hoping to get published. I look at everything I am sent. Most of the time it is not what I am looking for. Quite often I request pieces, as I explained the previous answer. It might be a particular instrumentation, or for a particular occasion. For example, I commissioned Ralph Shapey to compose a piece for flute and vibraphone for the opening of the Sylvia Smith Archive in 1992. There are several composers whose work I publish on a regular basis – Ben Johnston, Stuart Saunders Smith, Herbert Brun, and Robert Erickson.

3. How does the profit motive affect your choices as a publisher of serious music, about which you clearly care very deeply?

When I evaluate a piece for publication there are always both artistic considerations and financial considerations that often work against each other. I evaluate a piece in two separate stages. First, the artistic considerations. Is it worthwhile as a piece of music? Does it stand for something? Is there a point of view? Does it add something to the music world?

Then, separately, I look at the financial options. It is important to keep the artistic and financial considerations separate. You get into real trouble if you mix them up. You can’t think, “This piece isn’t very good because it would be too expensive to produce.”

4. Some of the scores you publish use non-traditional notation. What are the publishing challenges associated with unique notations and graphic scores?

The printing process is the same. What is different is that unique notations need more explanation as to how to use and interpret them. No performance practice has been established. The composer may be used to working with friends or like-minded people. It is very common that not enough information is offered, or the explanatory notes may be poorly organized, so that musicians who don’t know the composer won’t know what to do.

This becomes my job, and I have to be sure that I understand the piece very well. I try to imagine myself in the position of finding the score in a library 100 years from now when it is no longer possible to ask either the composer or the publisher. Is there enough information there, so that on its own, using just the publication, would someone be able to make sense of the score and be able to perform it?

5. Do you enjoy performing music that you have published yourself? Do you feel a greater attachment to these compositions?

I often learn and perform the music I publish. It is a great way to “test” the publication and to come to a deeper understanding of the work. I feel a personal attachment to the score, because I made it. But I didn’t make the composition.

6. Are there any musical philosophies that you promote through the music you publish?

Smith Publications supports live music on acoustic instruments. For the most part, I package all the materials needed to make a performance, including program notes if there are any. In formatting, I favor the needs of performing musicians.

My growing-up years happened before background music was so prevalent. There were times and places of real quiet and solitude. Nowadays there’s hardly a place you can go where you don’t have to hear a continuous stream of compulsory music. This situation makes live concert music not as special as it used to be. Moreover, people are used to the sound of artificial music – music that is delivered via a loudspeaker.

We live in a democracy. In public, we solve problems by voting and accepting the will of the majority, and this is thought to be good and fair. I have learned to look to the minority, and I am comfortable there. It is in the minority that the interesting ideas happen – the composed life versus the menu life. Ultimately, it is the minority that moves the culture.

If one loves music, it is not enough to just hear music. Part of what draws people to musicianship is to engage in a physical and aural relationship with a musical instrument. Electronic music cannot meet this need. Once it is made and preserved, there is nothing more that one can do with it. You can’t relate to it; only listen to it.

A musical score is to be interpreted. You can have a relationship with it. It asks for the uniqueness of each person who plays it. The performer must ask, “Who am I in relation with this score?” I try to choose music that will be rewarding for people to perform and hear, and which have many possible interpretations.

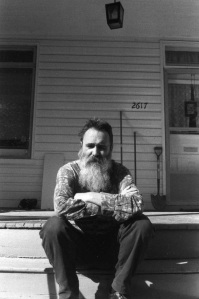

Stuart Saunders Smith

Questions for Stuart Saunders Smith:

7. Can you explain your compositional process? How do you begin a new composition?

When I compose, I use three types of thinking: fast thinking, slow thinking, and taste thinking. Fast thinking is intuitive, mythic, non-verbal, multi-directional, metaphoric thinking. Slow thinking is rational, verbal, uni-directional thinking, like I am doing by writing right here. Taste thinking is the mind of the senses. No matter how well fast thinking and slow thinking go, if it doesn’t taste good, it’s time to begin again.

Generally, I use all three types of thinking at once, like a rope made of three strands, with instantaneous cross-talk. Sometimes, I begin with fast thinking and flush out the idea with slow thinking.

I never use pre-compositional engineering plans to compose with. I want a music which can contradict itself and go off on tangents. I am not interested in consistency, which is what most pre-compositional plans guarantee. I am in search of magic, and like a magic trick, I want my hand to turn into a bird that flies away!

8. All your music is rhythmically intricate. Even your earliest pieces avoid duple rhythms, which have traditionally been the cornerstone of Western music. Why are they so rarely found in your music?

I instinctively recoil at duple rhythms. They push the pitches around like an assembly line. Duple rhythms block off time into equidistant units. The only interest such rhythms have is where the composer has tried to hide the downbeat with syncopation, or passages that obscure the duple world.

Politically, I associate duple rhythms with herd instincts – mass rallies of any kind. Large peace rallies are no different to me than a military band marching in unison. Both rely on a kind of hysteria deeply embedded in the human propensity for violence.

Music of rhythmic intricacy engages the listener each moment with uneven durations that cause a kind of stillness – a stillness that is deep below the surface of consciousness. Duples lead to trance with incessant movement. The stillness of music of rhythmic intricacy reflects the polyrhythmic nature of our mind-body experience. It leads inward to ourselves. The purpose of trance music is for us to leave ourselves in an emotional catharsis instead of centering us where we are.

9. As a composer, you have focused on the psychology of the performer. How has this influenced your composing?

All Western music notation is a symbol-system of graphic notation which musicians interpret. Furthermore, it is a pre-scriptive notation rather than a post-scriptive notation. I am keenly aware that when I am writing music, I am making a code which shapes the mind of the interpreter. I constantly ask, “How will my notational strategy be taken in?” The score indicates not just what to play, but how to play. Embedded in the design of the symbols are implicit meanings that literally shape the consciousness of the performers.

For instance, I have made many musical mobiles of various kinds. The performer often chooses or improvises how the vertical relationships will line up using fairly complex melodic shapes. The end result is a very complex web of counterpoint. Because it is a mobile, I get a high level of complexity, while the performer is alert and relaxed. In complex music, where the horizontal and vertical relationships are specified, the performer is often on edge. Relaxed complexity, edgy complexity, each have a different sound and a different effect on the nervous system.

10. Many of your compositions, for example Transitions and Leaps, are trans-media collective compositional systems. Could you describe these systems, and explain your inspiration for them?

I have composed over 135 compositions – mobiles, music of rhythmic intricacy, songs for speaking voice, music theater, and trans-media pieces. Three pieces are trans-media compositions: Return and Recall, Initiatives and Reactions, and Transitions and Leaps.

Trans-media compositional systems transcend performance media. These systems can be performed by actors, dancers, musicians, and mimes. Further, my systems are task notations. I notate a task, like “imitate an aspect of an event you have experienced in the system, making it higher, bigger, louder in some respect.” The symbols have to be general to accommodate all the time-arts, but be specific enough to be able to recognize the actions. My critique of scores that are largely drawings is that it is hard to tell one from another, listening to them. My trans-media scores are recognizable as that system from performance to performance. I was after flexibility and authorship, not flexibility and anonymity.

I came to invent these systems from a radio show about the cultural revolution in China in the 1970s. When it came to composing music, the proponents of the cultural revolution were suspicious of authorship – of the individual. For them, composition meant community-based activity. So their solution was to have one composer assigned to compose the melody, another harmony, still another orchestration, and so on. I thought Americans had mastered community music in jazz, country and Western, and rock. So I began to think of a way of capturing the process of collective composition where no one had to give up their identity while being part of a community project. I combined these ideas with a desire to contribute another look at total theater. That is how my trans-media systems were born.

11. You grew up in Maine, surrounded by unspoiled natural beauty. How have your experiences in Maine influenced your composing?

We have an expression, “Good fences make good neighbors.” Growing up in Maine, where I lived, meant being used to solitude. Behind my house were miles and miles of forest. After school I hiked alone. I became familiar with the rhythms of nature. Every day was the same, and different. As I got older, I tried to imagine what analog or metaphor in sound could be created from my observations of nature. My mobiles come directly out of my walks. The path is the same, but my look at it, one day to the next, creates a new path on the same path.

12. You have taught many innovative composers, like Will Redman and Kyong Mee Choi. How does one teach a student in the art of composition?

There is a music that only one person can compose. To find that music, it is often helpful to find a guide who has traveled those woods before. The beginning composition student needs exposure to a great deal of music and scores. The next step is helping the student to ask the same question over and over until their own individual answer arises. That individual answer to “What is composition?” is their beginning. Then I encourage the composer to forget what they know so that knowledge doesn’t get in the way of a music that only one person can compose. In short, I try to help the student compose private music, not public music.

Questions for Sylvia Smith and Stuart Saunders Smith together

13. Let’s talk for a few moments about notation. Do you think it is possible to compose with a specific notation, or does the compositional process require that one search for a way to notate a musical idea?

Sylvia Smith answers:

Western music notation is presented in music schools and in books as if it were a system unto itself, as if it were a neutral tool that gets used, a tool that one composes with. I used to believe that.

After many years as a publisher, a performer, and a listener, I have come to the understanding that, except in theory only, there is no such thing as music notation separate from usages of it. Notation is constantly being invented as it is being used, and so it is always personal and universal at the same time.

Now with computer notation software, we have for the first time such a thing as music notation, apart from its usage. And we see the results. The programmed notation acts like a straight-jacket of music grammar rules that one is expected to compose within. It has built into it the very things that ought to be composed. The compositional sketch is bypassed. The manuscript is bypassed. The personal usage of the notation is gone. I try to keep open to the possibility of composing something original using computer notation, but I have never seen it.

Stuart Saunders Smith answers:

A musical idea comes in its notation. It is a single concept. I do not invent a notation and then compose with it, or have a musical idea and search for a notation. The musical idea is in its notation; the notation is in the musical idea.

14. Stuart has used the term trans-media to describe many of his compositions, and has notated them in a very sophisticated manner. Could you explain the meaning of trans-media, and describe the nature of the notational system?

Sylvia Smith answers:

I’d like to address this question as a performer. I have made a realization of Return and Recall which I have performed many times. I have made realizations of Transitions and Leaps with several different groups. These scores invite you to think differently about music-making and about performance.

The term “trans-media” means that it transcends a single performance discipline. The notation applies to any of the performing arts. Put very simply, Transitions and Leaps is about how one moves from one category of information to another. This is done by either a gradual transition or a sudden leap, like a jump-cut in the movies. The first thing you do in developing your realization is to establish four categories of information/activity. Some of the categories we used were: nostalgia, Old English, Bach, piano interior, Japanese Haiku, radio sounds. The score of Transitions and Leaps uses ideograms that stand for basic concepts that apply to any of the performing arts – directives such as high, low, accelerate, develop, imitate making it shorter, etc. The results are both abstract and related, and make a relatedness among different disciplines in the performing arts.

Using the Transitions and Leaps score, it is possible to make a piece combining different disciplines, such as music and dance, where one discipline is not relegated to a mere accompaniment to the other. Most dance is accompanied by music in a functional or supporting role. Early on, I was attracted to the work of John Cage and Merce Cunningham, and I still am. And yet it never seemed quite enough to have music and dance merely co-exist, separate but equal. I always wished for some kind of intentional relatedness, even though abstract. So I am very eager to work with musicians and dancers and actors together with these trans-media systems, where each discipline is both integrated and allowed to have its own integrity.

15. We have spoken a lot about music and politics. What is the relationship between music and politics?

Sylvia Smith answers:

Growing up, I was taught not to be taken in by the herd mentality. Television was kept out of our home, although occasionally I watched it at friends’ houses. I never developed the television habit, or the habit of always expecting to be entertained. I am never bored. There is always something to hear; something to think about.

In high school I was particularly moved by the writings of Thoreau. He offered solutions to a lot of contemporary problems, then and now. He also composed his life. I have always tried to lead a composed life – thinking things through, not giving in to the taste industries, not acting out the scenarios shown to us on television, thinking outside the box, and in music, having another idea – a personal idea – about how it should sound.

The composed life is a political position. It puts you at odds with society, maybe a little, maybe a lot, maybe you are in trouble with the law, maybe you are shunned. Maybe you become a leader in a particular area.

One of the most disturbing changes I have witnessed within my lifetime is the change in music – becoming more and more of a commodity instead of something you participate in – something you buy rather than something you make and do. Music literacy is at an all-time low. Not only the ability to read a music score, but to have some familiarity with music literature.

The Floating Hierarchies, by Herbert Brun, is an example of a successful political piece, calling for a different kind of arrangement among the players. Each performer composes a realization of graphic images for the group to play, and then another performer does the same for the next movement, so the hierarchical arrangement between composer and performer is retained, but shared. No one is at the top of the hierarchy for long, and everyone gets to be a leader and a follower at different times. This arrangement seems to be a much more effective political and social statement than the typical political song involving words set to popular-sounding music.

Stuart Saunders Smith answers:

Herbert Brun, who was one of my composition teachers, had a description of the political role of the composer that I agree with. One type of music reflects the values of a society. This music is an output of the society. Another type of music creates new values in the context of a society. This type of music is an input to the society. Input music at first creates nonsense, which becomes a new sense. Then after a while it becomes common sense, an output. Creating music outside of community music can shift the society by giving it new meaning. Private music made public (performed for an audience) becomes slowly part of the community rather than a reflection of the community. Overt political music, like worker songs, are a reflection of known political values. Such songs do not on a fundamental, structural level, change how we think. These songs function as vehicles for solidarity.

If the music is private, it can move a society. If a music is public, it can describe a society. Art music moves, popular music reflects. Aspiration versus affirmation.

16. What drives you to live ecologically mindful lives and choose a vegan/vegetarian style of eating?

Sylvia Smith answers:

Being a vegetarian is another aspect of leading a composed life. First do no harm. I have been a vegetarian most of my life. I became a strict vegetarian in 1970, abstaining completely from eating any animals. Other kinds of shifts happened that I did not expect. The first shift was social. One has to relate to others who are not vegetarian, and are perhaps threatened by it. One has to constantly negotiate with institutions – school lunches, for example, hospitals and dieticians, the teaching of nutrition as it is taught in schools. One becomes aware of how the dairy and meat and sugar industries shape public opinion and public policy about how and what we should eat.

Within a year, another shift happened. I had a different relationship with animals, being more sensitized. I felt strongly that we need to share the planet with other life forms. It is much easier to be a vegetarian now than in 1970. Vegetarian eating is looked at as a viable option, even though it is still seen as an alternative way of eating.

Stuart Saunders Smith answers:

I give the following advice to my composition students: Do not take illegal drugs. Get plenty of sleep. Eat a healthy diet; a vegan diet is best. Compose the same time every day. Get plenty of exercise.

17. What are the advantages and disadvantages of being both a married couple and also in a composer/publisher relationship?

Sylvia Smith answers:

Stuart and I are husband and wife, composer and publisher, composer and performer. I always have to guard against mixing up the roles. For example, if we have just had an argument about a household matter, I can’t let that color my judgment about publishing decisions.

As a percussionist, I often perform pieces that Stuart has made. Because we live in the same house, I have the privilege of hearing each piece as it is being composed. This gives me a deeper understanding of the music. Stuart has made many wonderful percussion pieces that I am honored to perform.

I tour with Stuart’s percussion theater music. It is the only percussion theater music I can find that is worthy of my time and effort. Typically, other percussion theater music involves joke-telling or silly gestures like waving the mallets in the air. Stuart’s theatrical music is centered around a text, with the instruments used sensitively and appropriately. I never feel like I have “used up” one of Stuart’s pieces. I come back to them over and over and my experience and understanding gets deeper and deeper. Some of them I have performed over one hundred times.

Living in the same household makes collaborations of all kinds easier. One of our most successful collaborations has been A Viet Nam Memorial, a duo for narrator and vibraphone. I wrote the text in 1991 after a visit to the Viet Nam Memorial in Washington, DC. Using that text, Stuart composed a part for vibraphone and triangles. There are times when the text stands alone, times when the music accompanies the text, and musical interludes without text. My texts work well in a musical setting, because I always write texts with sound in mind, meant to be read out loud.

Stuart Saunders Smith answers:

There was a time, back in the early 1970s, when I had three publishers besides Sylvia’s Smith Publications. By comparison, her company had better distribution, advertisement, printing, and paid royalties on time. I got out of my contracts with the other publishers and asked Sylvia if she would represent my music as a whole. She agreed.

At first, many people assumed I was published by her because we are married. This was never the case. Sylvia wants and wanted to publish my music for her own reasons. Now the situation is somewhat different. Her company has grown so much that people do not connect us up by last name. Smith is such a common name that many people make no assumptions. In fact, some people have asked Sylvia if I am still alive!

I find it exciting living with a publisher. It is wonderful to see her sell music to people from exotic, far-off places. I have always thought that publishers are one of the most important cultural institutions in the Western world. Publishers quite literally make history. By making private thoughts public, a publisher contributes to the dialogue about ideas and how they can grow. I see scholars researching composers that Sylvia took a chance on decades ago.

Further, a publisher can determine the content of the future. Smith Publications has become a prestigious publisher by concentrating on radical music made by composers who have the skill, creativity, and craft to make their radical music well-defined, clear and convincing. In this age of the internet, many people question the need for publishing. Primarily a publisher chooses. A publisher is a gate-keeper. What a publisher does not publish is as important as what is published. Who wants to try to sort out among 1,000 composers, when a publisher you trust has already done that!

18. On a final note, what message would you like to send out to the next generation of new music performers, composers, and publishers? What is your advice to them?

Sylvia Smith answers:

Take care of your body just like you take care of a musical instrument. Eat well, eat vegetarian, exercise, rest. If you play an instrument, invest in your body – zero balancing, Alexander technique, Rolfing, yoga, as often as you can afford it. It will pay off right away, and in your later years.

Stuart Saunders Smith answers:

My advice to composers is when composing, always tell the truth. Compose out of your experience rather than your learning. New music is not a style or genre. It is a way of life – a life of composing from the inside out. Composers are leaders. Be sure that the direction you are leading is a place you want to live

Discussion

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

Pingback: Stuart Saunders Smith - February 13, 2013